Diedrick Brackens’ Invitation

In the early months of 2020’s Covid-19 shutdown, Diedrick Brackens and I had a conversation about the significance of Juneteenth. We were both locked-down in Texas. Zoom calls had not yet found that indelible position in our lives so we chatted by phone, like the olden days. The thirty-minute conversation was easy and friendly as we exchanged accounts—absurd, poignant, tragic, celebratory, and otherwise—about the holiday, which, rooted in Texas history, has significant ties to Diedrick’s own family in Mexia, Texas. We also marveled at how a Global pandemic had changed the world overnight. I spun around and around in my chair, laughing as we each described what happens when we tell people that Texas is our home; reactions range from what could feel like a condolence or a joke. As I wrote in an essay for Hyperallergic, Diedrick said, “Texas has this reputation of being racist and homophobic. But other places are all those things too. It’s just coded differently.”

Thinking back, I imagine a long silence when he said this—because this might have been the first time I considered the ways in which we are, or aren’t, invited to understand the code. I suppose I never thought not being aware of the code was an option. Many of us learn codes out of necessity, code-switching automatically with little thought. But Diedrick’s comment suggested there is always a choice: pay attention to the cues, or not. Learn the language, or not. Look at something from all sides, or not.

For people from marginalized communities, recognizing the code, and code-switching, isn’t new. We do this every day, often subconsciously, as we try to determine where, or how, to find secure footing. But Diedrick’s acknowledgment that Texas is just coded differently seemed to come with an invitation to learn the code; like, We have this special way of doing things in Texas, check it out. As if understanding the code is an opportunity or a gift.

To be clear, I’d been learning the Texas code since I’d moved there a decade or so earlier, but more out of survival. Diedrick’s words, however, shifted agency back to me. We couldn’t see each other through the phone, but I felt so seen.

This was the first time we met.

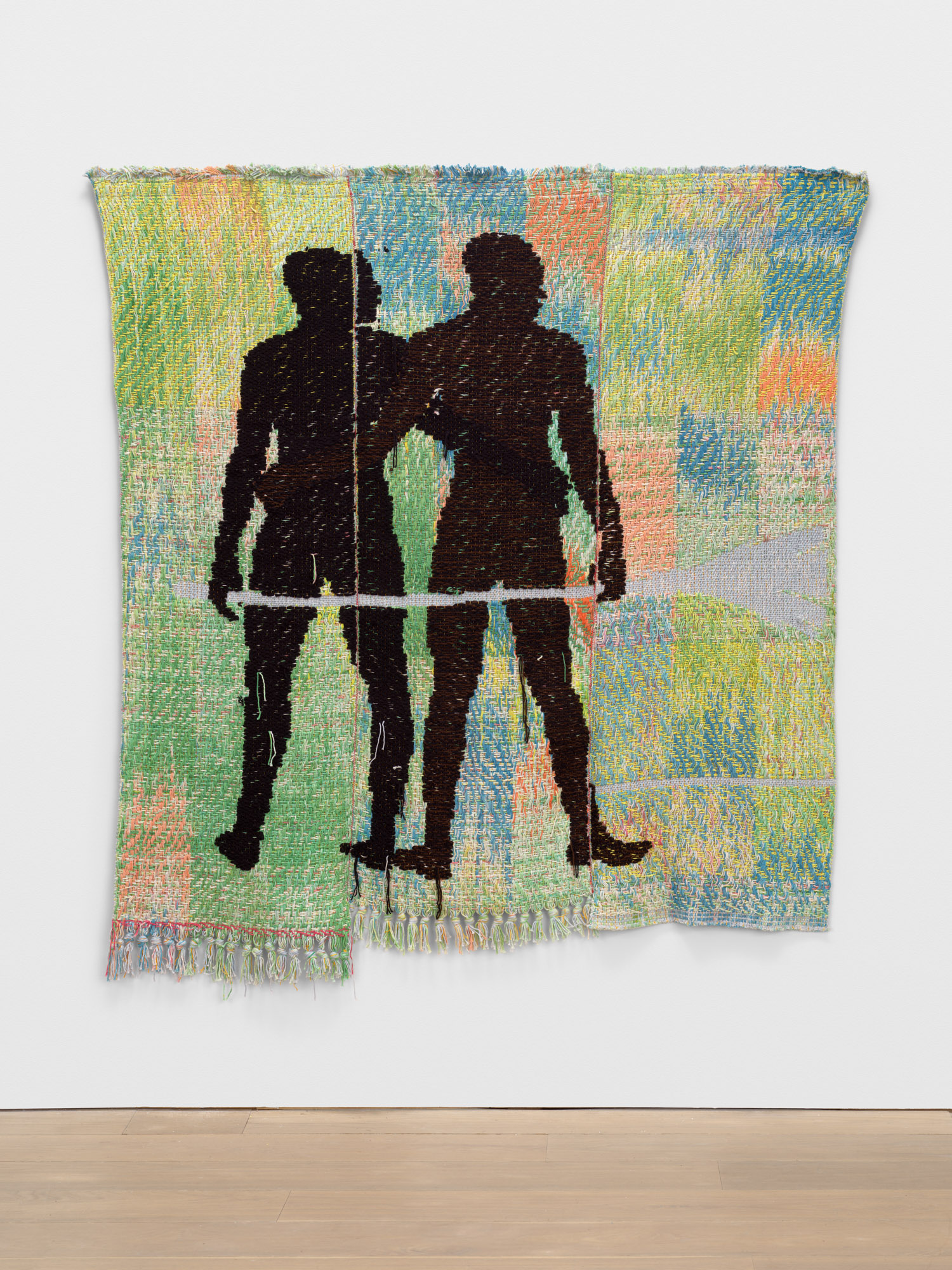

profound in meaning, histories and myths that don’t end, or start, on that woven plane. Central figures, often represented as silhouettes, often black, crouch and bend, stand in power and vulnerability, recline thoughtfully, or extend a hand tenderly in balanced proportion to the muted purple, rose, green, and gold rooms, landscapes, and other worlds Diedrick builds for them. The figures include people, farm animals, catfish; each seemingly determining their relationship to one another, even when a figure stands alone.

In May 2024, in a conversation with Essence Harden, Diedrick said, “There are several things in the practice that are right on the surface for people to see and unpack, but not everyone does. And sometimes I can’t tell if that is because they don’t see it or they would rather talk [not] about it.” In Texas, there is something to be said for seeing what’s on the surface and leaving certain things unsaid. But Diedrick’s work says: It’s okay to see what you see. It’s okay to feel what you feel. My work (maybe like Texas) is coded differently—there for you to read, if you’re willing.

In the same conversation with Essence, Diedrick discusses the decision to show the backs of certain tapestries, explaining how, “Oftentimes the figures don’t show up on the back, they don’t register at all. So it’s almost like seeing the landscapes without the people in them and then seeing the landscapes with the people.” This notion fascinates me: a prompt to consider how I might show up in a space if the people were removed, or vice versa. When I read a room, what am I reading? The environment, the people? Both? Does one element carry more weight than another? But it also makes me consider that Diedrick’s decision to reveal the back of the work is a further opportunity to understand his code. He tells Essence, “There’s this emotional register to being able to see the back, as well as giving the viewer even more information, more access.” Does this provision of access reflect the access we seek in our everyday? Further access to cracking an array of codes? I’d like to think that by showing us both sides of a tapestry, he is modeling how we always stand to look further.

In a video recorded at Indigo Arts Alliance during his residency in 2023, Diedrick, who is also a poet, says, “I’ve always written as part of how I make sense of the world.” He explains, too, that for him, weaving and writing are so intertwined, it can sometimes be difficult to pull the two apart, even noting that the words text and textile share a root: the Greek word texere, to weave.

Although the tex in Texas has nothing to do with the Greek word, his upbringing there embedded the code he would rely on to understand his surroundings, interpret stories, and maybe tell stories—it’s looped in and out of his tapestries and poems. “I do feel that I’m building, or encoding, something into the threads,” he says in the video recorded during his residency. In his beautifully poignant poem, “I Fed My Husband My Ears and Fled,” Diedrick gives us a hint at the way he indexes his world: a broken and restless body can be perceived as flight, stardust, lakes on fire, mathematics. And heaven is a muddy riverbed.

The second time we spoke—and the only time we’ve met in person—was years later, crossing paths at an art fair. He was going, I was coming. I recognized him from social media and the press, and stopped him like a fangirl. After explaining who I was, we fell into light conversation as people bumped into us or stepped around us. He told me he was doing a reading that night, and I told him I would try to attend. Before saying goodbye, we took a selfie and I told him I would see him later, but I didn’t make it.

All things considered, we’ve not spent very much time with each other. Yet as we discussed in our phone call, we’re both well-practiced at reading between the lines. (Perhaps because of the time we’ve spent in Texas.) As such, I have filled in much around these relatively short exchanges—sitting with his words that are as intentional as each of his carefully placed threads—as I continue to move from one code to the next. Our conversations are perhaps a reflection of Diedrick’s work: an invitation to take it all in, to discern what you’re able, and decide what to pay attention to, accordingly.

LISE K. RAGBIR

Lise K. Ragbir is a writer, curator, and the Co-Founder and Managing Partner of VERGE. Her essays—which lie at the intersections of race, identity, and culture—have appeared in Hyperallergic, Frieze, Artnet, The Guardian, Time Magazine, USA Today, The Boston Globe among other publications. She is also the co-editor of Collecting Black Studies: The Art of Material Culture (2020,) University of Texas press. Her works of fiction have been featured in Catapult, Intellect in the UK, Pree Literature, and more.