Ebenezer Akakpo and

Eneida Sánches

An Experience in Exploration

Ebenezer Akakpo prefers to have the idea for whatever he is making fully formed in his mind before he begins constructing, with all the problems he can foresee worked out ahead of time. He is a jeweler and designer who has developed an innovative line of bracelets, earrings, and home goods that feature iterations of ancient West African symbols known as Adinkra. He has always been the kind of artist for whom planning and structure are essential to his creative process.

When he met Eneida Sánches, a Brazilian metalsmith, printmaker, sculptor, and installation artist, one of the first things Ebenezer noticed was that their approaches to making art were very different. Ebenezer liked to begin from a blueprint. Eneida’s practice was almost the complete opposite—starting with a simple object or an idea and letting her creativity and surroundings lead her in unexpected directions. As a mentor, Eneida encouraged Ebenezer to “let go” and experiment, to try new ways of seeing, situating and imagining his work. She brought a ludic, or playful, quality to their mutual experimentations and Ebenezer said he felt free to explore perspectives and techniques he had only dreamed of previously.

Eneida Sánches and Ebenezer Akakpo were the inaugural mentor and mentee pair for the Indigo Arts Alliance Artists Residency. They worked together in Maine in June and July 2019. The choice of Eneida as the initial mentor was strategic. A native of Bahia, Brazil, Eneida began her career as an architect and eventually extended her creative work into other areas of studio art. She is an established artist, exhibiting and teaching within Brazil and internationally; and her experience includes several previous residencies. She also served on the board of directors of the Instituto Sacatar in Bahia and has long nourished a desire to establish a residency on her farm in the Chapada Diamantina region for Afro-Brazilian and African American creatives. Eneida’s feedback would be particularly valuable because she understands the need for an institution like Indigo Arts Alliance, and more particularly, for the space and opportunity a mentorship program under Black leadership provides to artists of color.

While she and Ebenezer worked together, Eneida was also preparing a collaboration with Daniel Minter. It is a project that involves the creation of a forest-like physical environment combining images of plants and trees with tools of human interaction with the natural landscape—tools and technologies that have particular meaning for the history of people of African descent in the Americas. Railroads, for example—symbols of migration, industry, and geographic separation—also represent a kind of liminality, especially in their connection to religio-philosophical principles known as orixá; in the Afro-Brazilian ritual tradition, Candomblé. Describing the project, and her process more broadly, Eneida experiences her work and the surrounding world as an “atmosphere where everything talks to everything…It’s all integrated.” This concept and approach has similarities to Daniel’s own orientation in recent work like Quantum Exchange—where he represents the talking and listening that is continually happening at cellular levels in all of us.

In Maine, Eneida was exploring plants as symbolic language and as carriers of story. In Afro-Brazilian context, certain plants are understood to have specific spiritual properties. Eneida drew a long horizontal sansevieria, or snake plant, with an ear at the end of its pointed leaves. Known in Brazil as espada de Ogum (Ogun’s sword), the plant was named for its bladelike appearance and for its ceremonial connection to the orixá of metal, railways, and other transportation, technology, and pathbreaking—Ogum. Back in Brazil at the outset of the COVID19 pandemic, Eneida experienced the uncertainty and sadness of the global situation and she was unable to do any art in her home studio for many months. One day, as she thought about what she needed to move beyond the stasis and anxiety, Eneida remembered the images of plants she had been making during her Indigo residency. There were seven in particular, medicinal and ritual plants from the Candomblé tradition that she began to draw again, in different sizes and media: some as graffiti, some with small pieces of metal attached, some in charcoal. And the plants began to help her. These were plants that, in the healing rites in Candomblé, would have perhaps been included in a curative bath or made into an incense to provide purifying smoke. Eneida drew them. For her, the drawings had restorative capacities—the energy of the plants that would otherwise have been released in the water of a banho de folhas reached her via the process of making the images. In the midst of political and public health emergencies, where many people were afraid and manipulated by fear, she said the plants were a reminder that we, humans, can find/make many ways to heal ourselves, to keep ourselves connected to the grounding energy of the lifeforce.

This is part of the importance of the Indigo Arts Alliance. It is a place that acknowledges, and in fact emerges from, the traumas of our global history—the traumas of the plunder of land and people, of the inequities that live inside the quotidian structures of our cities, our countries, our institutions, our lives. And because Indigo knows these things are true, it is not afraid to look at them. It is not afraid to hear and see the stories that others sometimes fear. But just as important, if not more so, the artists of Indigo come from the places and people who have survived the trauma, who are in this very moment as we speak, surviving the trauma—even as it kills them. Yes, you read that right. We die every day. And we still live.

And what makes that possible? The gathering. The gathering of artists from all the hidden and excluded corners. But not just the artists, but the ancestors of the artists—their histories, with all their wounds and their wisdom. With all their tenderness and genius and rage. With their abundant and anguished joy. If an arts institution has no room for the ancestors of Black and Brown people—the bones that lie under the Atlantic Ocean; the bones buried as coffles and marches made their way across the land; the bones now breaking and buried from jails and prisons and buildings with no sign outside but screams inside. If an arts institution has no room for the fullness of humanity in the modern world, it will not be useful to those now gathering. If an institution cannot acknowledge the whole history of all of us together, and if that acknowledgment does not shake the institution at its foundations, it cannot make room.

Black and Brown artists come with their families. Invited or not. They come with ghosts. And there will be feasting. And welcome. And laughter. And wailing. And music. And dead silence. And people will dance. And the bones will dance. And the numbers have no end. And only places who acknowledge that this is the history we share—that we must make a future from the wisdom of bones—are ready.

As visually different as their works may appear, Ebenezer and Eneida are both employing symbolic languages grounded in African and diasporic philosophical understandings. Both artists were raised in cultural contexts where African religious and cultural symbolism abound—Ebenezer in Ghana, West Africa, and Eneida in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil: places that hold ancient and important understandings of the world. Places with insights and compassions from which all the world might benefit and grow and transform. With different processes and in different forms, the jeweler/designer and the printmaker/metalsmith are exploring ways to demonstrate the interconnections among human stories and communicate fundamental and shared human experiences through codes and concepts of Africa and the Afro-Atlantic experience.

In the mentorship, Eneida focused on trying to help Ebenezer detach his creative process from the idea of developing a specific product as the end result. A computational designer, Ebenezer likes to do work that solves problems, work that has a specific and useful finality. Instead, Eneida encouraged her mentee to simply focus on the experience of creating, to allow himself to develop another kind of relationship with his work: not “wanting something” from it, but just exploring where it might go when he was not thinking about results. It was a liberating approach for Ebenezer.

When he first immigrated to the United States at the beginning of his career, Ebenezer’s goal was developing a line of jewelry for the high-end luxury market. During a period of study in Italy, he noticed the ubiquity of certain symbols, like hearts, for example, as key design elements in the work of the Italian jewelers whose stores and workshops he visited. The heart-shape is similar to the Akoma symbol for patience and tolerance in Adinkra iconography and the connection planted a seed in Ebenezer’s mind about possible uses of that extensive African conceptual resource in his own work.

Later, as a student at the Rochester Institute of Technology, Ebenezer visited the Cooper Hewitt Museum for an exhibit on sustainable design that left a strong impression on him as both an artist and designer. In a lecture associated with the exhibit, he learned that companies designing for the global luxury market target only 10% of the world’s population. Ebenezer wondered about the other 90%. Walking out of the Cooper Hewitt that day, he began to question his desire to focus his work on high-end luxury products: “That was where I started thinking—how else can I use design to solve problems?”

He settled on a project to create small-scale, portable water filtration systems that can be easily used in rural communities in his home country, Ghana. The Adinkra-based jewelry designs emerged as a way to get local villagers excited about the water filtration project but Ebenezer quickly recognized the broader global appeal of the concepts and values represented by the Adinkra symbols.

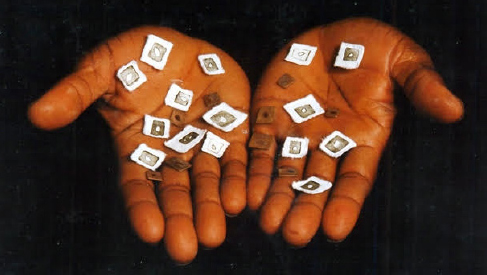

The iconography that is the signature of Ebenezer’s work are representations of centuries-old West African values, first codified by the Bono people of modern day Ghana and Ivory Coast and shared widely among other Akan groups. There are dozens of signs in the Adinkra classification, each associated with an idea central to Akan ethical and cosmological systems, often expressed in a proverb. Concepts like Agreement, Endurance, and Sankofa (wisdom in learning from the past) are represented by specific ideogrammatic forms. Ebenezer explores these symbols in different sizes and iterations, colorings, positions, and products—focusing on the connection between the image and the concept it expresses.

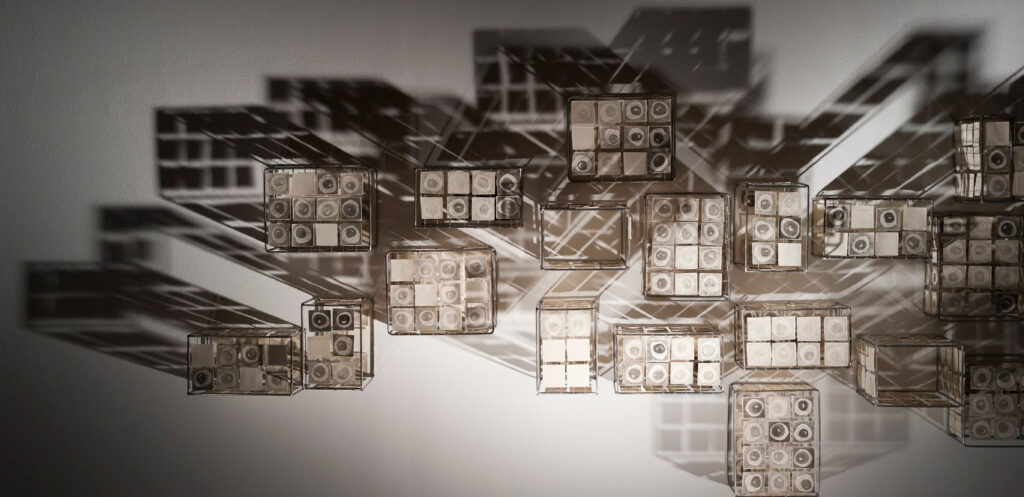

During the Indigo residency, he was able to digitally shift and scale the Adinkra symbols to get a sense of how they would look as ten foot tall structures: a single pattern, repeated and spaced out on the screen as if reverberations or slices, so that the shapes look almost terrestrial, like large natural formations of earth, or giant ocean waves. Or like vertebrae; a spine. Ebenezer would bring to the studio big 3D printed models of some of the symbols and Eneida would play with them, wiggling them and holding them up to her ear or her arm, or have Ebenezer shine light through the spaces in the designs so that shadows fell on Eneida’s clothes or on the walls. The point was simply to play and it was this freedom that Ebenezer said he particularly enjoyed: the experience of exploration without concern for output.

The process of untethering her own creative work from specific, desired ends is something Eneida also went through, in the early 2000s, after almost a decade as a ritual metalsmith, creating ceremonial implements for Candomblé temples and the personal altars of devotees. “When I was creating the ferramentas, the orixa tools, it was very much my target to have specific orders and to sell them.” Her crowns, brass and silver-plated mirrors, double-headed axes, and other symbolic objects were commissioned by some of the oldest Afro-Brazilian ritual communities in the country. It was a work Eneida felt called to, and that she enjoyed. But after a while, she tired of it. It was repetitive and she wanted to do something else. At the time, she thought she would move completely away from work related to the African spiritual forces, the orixás, and she instead decided to study French and German philosophers and the filmmakers Wim Wenders and Glauber Rocha. One film in particular, Rocha’s Terra em Transe, [“Entranced Earth”] struck her powerfully. The film is a masterpiece of Brazilian cinema: a non-linear, dis-synchronous allegory of political deception and the loss of naivete. It is also a film whose structure imitates trance.

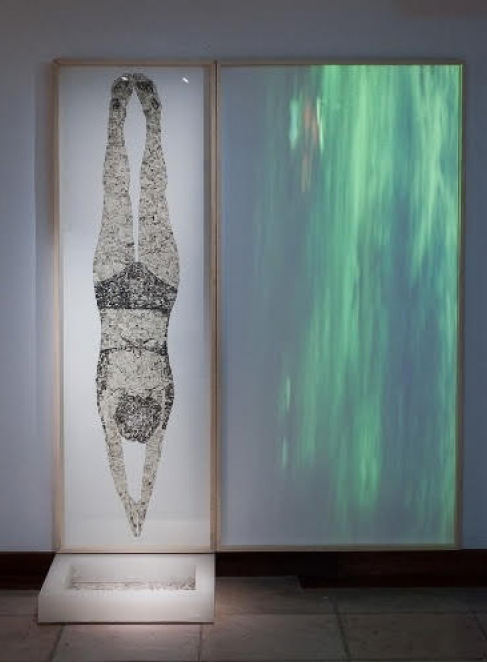

The trope of trance in the film supported Eneida in thinking about liminality, communication, and materials in new ways. Trance is an elemental experience in many African and Afro-Atlantic religions, and ultimately, it is a poetic-artistic means of communication between different planes of experience. Critic Solange Farkas writes that Eneida was moving away from the specificity of the symbolism of the ferramentas and toward “a less literal representation of Candomblé…” Her encounter with Glauber Rocha encouraged Eneida toward greater fluidity, and even dilution, in her use of Afro-Brazilian symbolism. In that process, Eneida’s work has become increasingly an experience of translation, of moving across dimensions and through displacements. She talks about master artists like trumpeter Miles Davis and samba singer Clementina de Jesus through whom we can understand what happens, artistically, in trance states. Eneida sees the liminal intensity of artists—when they are operating from a certain orientation, from profound engagement with their own creativity and with the lifeforce in their work—as enabling them to transmit understandings, insights, visions, images…bringing what they see, what they experience to a plane where it can be shared.

For Eneida, one of the most valuable aspects of the residency at Indigo was the opportunity to strengthen her capacity to talk about her work, to champion her own artistry and to interact with curators, museum directors, collectors, and other arts administrators from a position of confidence in the value of her work. “This is so important for us as Black people,” she said. “[As] an artist who is in mid-career, or even beyond mid-career, I should respect and defend my work, and I should care for my work.” Eneida credits Marcia Minter’s depth of professional experience in the world of art and design and the interactions and conversations into which she invited Eneida; these served as practical instruction and models for the visiting artist. These rich interactions add multivalent layers to the mentoring, the sharing, the growing that the residencies provide.

Perhaps it is especially fitting that artists from the breadth of the diasporas of Africa and the Indigenous Americas can find a common space in the physical and aural environs created by the Indigo Arts Alliance to be together. Not under the auspices of vetting and exclusionary structures, where the insights of Black and Brown people are almost automatically denied and the wisdoms never assumed. But instead, just spending time: riffing off of one another, creating, imagining, seeing relatives and friends in one another’s hands and faces—not running from the hard histories but sharing all those stories, the things we have learned across these many centuries of modernity (and before) about how to survive a hard place and make it beautiful.

ENEIDA SÁNCHES

Eneida Sánches is a visual artist from Bahia, Brazil with a degree in Architecture from the Federal University in Bahia (UFBA). Her return to the visual arts was inspired by her interest in the tools for working with brass and copper for religious purposed when she was an apprentice to the Bahian master toolmaker Gilmar Conceicao. Starting in 1992, she began exhibiting these objects in art galleries in and outside of Brazil.

In 1997, as an auditor in the Master’s program at UFBA and, subsequently, through workshops at MAM Bahia, Sánches would bring these different forms of constructive thought together. The combination of architecture, the tools of the orisha and the metal etchings are what has allowed her to make works like those exhibited in Transe, deslocamento de dimensões. Sánches’ production explores the idea of Trance as a religious phenomenon and the collective social representation of Afro-Bahian culture and its histories. Her iconographic repertoire originates in the universe of Candomblé ritual and its functional order. Her ten thousand prints result from hundreds of copper plates and the convergence of the functional limits of etching and sculpture.

EBENEZER AKAKPO

As a child in Ghana, I could never have predicted the path of my future. Today, I know that the only way to understand who we are is to connect the dots backward to the events that made us. Every items I design carries pieces of my cultural history, skills, and techniques of my education, and the passion I carry for promoting social justice. They are meant to remind us to remain open to every experience life brings us – they each have significance in who we become.

Design can often be interpreted as a luxury for the wealthy. But it is my mission to use design as a tool to solve problems. The creation of the Akakpo line has allowed me to combine my multi-faceted educational experiences with this desire to affect positive change. I am able to use the traditional and cultural power such as designing a portable filtration system with B9 Plastics to purify water for the people of my native Ghana.

DR. RACHEL ELIZABETH HARDING

Rachel Elizabeth Harding is a poet and historian. A native of Atlanta, Georgia, Dr. Harding teaches in the Ethnic Studies department of the University of Colorado Denver and writes about religion, creativity and social justice organizing in the experience of people of african descent in the Americas. She is author of two books: A Refuge in Thunder, a history of the Afro-Brazilian religion, Candomblé; and Remnants: A Memoir of Spirit, Activism and Mothering, co-written with her late mother, Rosemarie Freeney Harding, on the role of compassion and mysticism in African American activism.

Dr. Harding is an egbômi (ritual leader) in the Terreiro do Cobre Candomblé community in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil where she has been a member for over twenty years. Harding’s honors include a Cave Canem Fellowship, the Sterling Brown Distinguished Visiting Professorship at Williams College and an honorary doctorate from the Starr-King School for the Ministry.

Edited by Jenna Crowder

Jenna Crowder is a writer and editor. Her writing has appeared in

Art Papers, Boston Art Review, The Brooklyn Rail, BURNAWAY,

Temporary Art Review, and The Rib, among other places.

jennacrowder.com