On Wordplay, Rhythm, and the Art of Ryan Adams

It was Ryan Adams who reminded me that it’s possible to get to know an artist’s work without ever stepping foot in their studio or standing in front of their work in an exhibition space. There’s a way to feel familiar with an artist’s practice without having their murals be the backdrop of daily commutes or perusing their work on digital screens. What I consider to be my introduction to Adams’ work didn’t actually involve his work at all. It happened this past January, by happenstance, in the kitchen of Surf Point Foundation during the first week of our residency, as we both brewed our coffee. Though the curious curator in me looked into the work of the other artists in my residency cohort before I arrived, those explorations didn’t tell me nearly as much as my conversation with Adams did that morning.

After sharing the journey we each took to get to Surf Point–me through a multi-day road trip from Chicago, Illinois and Adams through some creative family scheduling from Portland, Maine–the conversation turned to music. From there, we quickly discovered our mutual love and appreciation for hip hop, particularly lyricists Phonte and Big Pooh who are also known as the Durham-born duo Little Brother.[1] I bring this up because, in most cases, to be a Little Brother fan signals a reverence for poetics, clever wordplay, humor, alluring rhythms, and unapologetic respect and devotion to Black life and culture. Similarly, to bear witness to Adams’ work, no matter the context, is to experience all of these same qualities echoing in a different yet deeply related form. When I look at Adams’ art now, it is always lyrically and sonically annotated. I let myself fall into the words and get caught up nodding to the beat.

Many months later and as he prepared for shows at Notch8 Gallery and Ishibashi Gallery (Concord, MA), Adams and I took some time to discuss the origin story of his style, making work on the streets versus the studio, and what it’s like to be a Black artist in an era of seismic social, political, and cultural sea changes.

Tempestt Hazel: I’m always curious about origin stories. Can you tell me about who you are and your background, especially as it relates to your practice?

Ryan Adams: I was born and raised in Portland, Maine. It was rare to have Black folks up here when my grandparents on my mom’s side moved up here from rural Mississippi. Things were just extremely dangerous [at the time]. An incident happened when they were pregnant with my mom, and basically one of my great aunts had already moved to Maine to get as far as possible away from rural Mississippi. My grandparents packed all their stuff and took off–they actually had my mother on the way to Maine. They came to Maine in the early 1960s.

Growing up here was unique on a few fronts. Being the only Black person in the room very often was the case. My family on my mom’s side came from the thick of Mississippi. They were strong folks and taught me to take no bullshit. Though this place was different–as in blue collar–there [were] so [many] terrible, unfortunate racist things I had to put up with–but [I feel like my family] prepared me for that.

We were one of very few Black families–we all knew each other. It was an interesting upbringing. I give my mom a lot of credit for making sure I saw the world outside of this place.

My father came up here by himself, too. He was raised in the Connecticut and Massachusetts area. He was a union pipefitter and found a job up here. He would tell me how he wasn’t planning on staying, then he met my mom. They had me in 1984.

Painting, drawing, and comics have always been my escape. It puts me in my own world. I was a latchkey kid, my mom was a single mom, and she would tell me about how she would come home and I would have papers and comics sprawled out on the floor, and I would be drawing. She remembers it so vividly. I had favorite illustrators at age nine. I would study things and redraw things from [comic artists like] Tex Avery or others. I was into it on a pretty deep level.

TH: So you were simultaneously in an environment where your creativity was being nurtured at home, but then the world outside of your home was a challenging place–especially being in a state that has one of the smallest populations of Black people. Given that environment, what was it that made you able to envision a career as an artist?

RA: I really didn’t. All growing up, my mom’s side of the family who lives [in Maine], who I was with the most growing up, [were] very academic. At the time, I was the only grandchild, so I was encouraged to go into one of the cookie-cutter careers. Being an attorney was where I was headed.

Honestly, I had no idea that a career or livelihood in the arts was an option until maybe a few years ago–six to seven years ago. I always thought it was something I had to do on the side to feed my soul. I didn’t want to be doing business development or sitting in painful meetings. But, [in the past few years,] I got to a point where I believed I could figure it out–having a career as an artist. I didn’t really have that direction as a kid. Though my art was supported, it was understood to be a hobby, not a career option.

TH: That’s a really surprising response, but also understandable. I feel similarly. I think we both have that experience of working in areas of the arts that are often viewed as more stable–like in arts administration, and then recently–finally–taking the leap to do our creative work full time. Your response is not what I was expecting, though!

RA: On my father’s side, that’s where the artistic side of me came from. There are phenomenal artists and painters. My uncle Charles was a very well known oil painter in the Virgin Islands–his paintings were absolutely beautiful. [Even so], I never thought it could become a career.

TH: This next one is a two-part question: First, over the span of your practice, how has your work evolved, especially as you started defining your own style and began taking steps to becoming a full time artist?

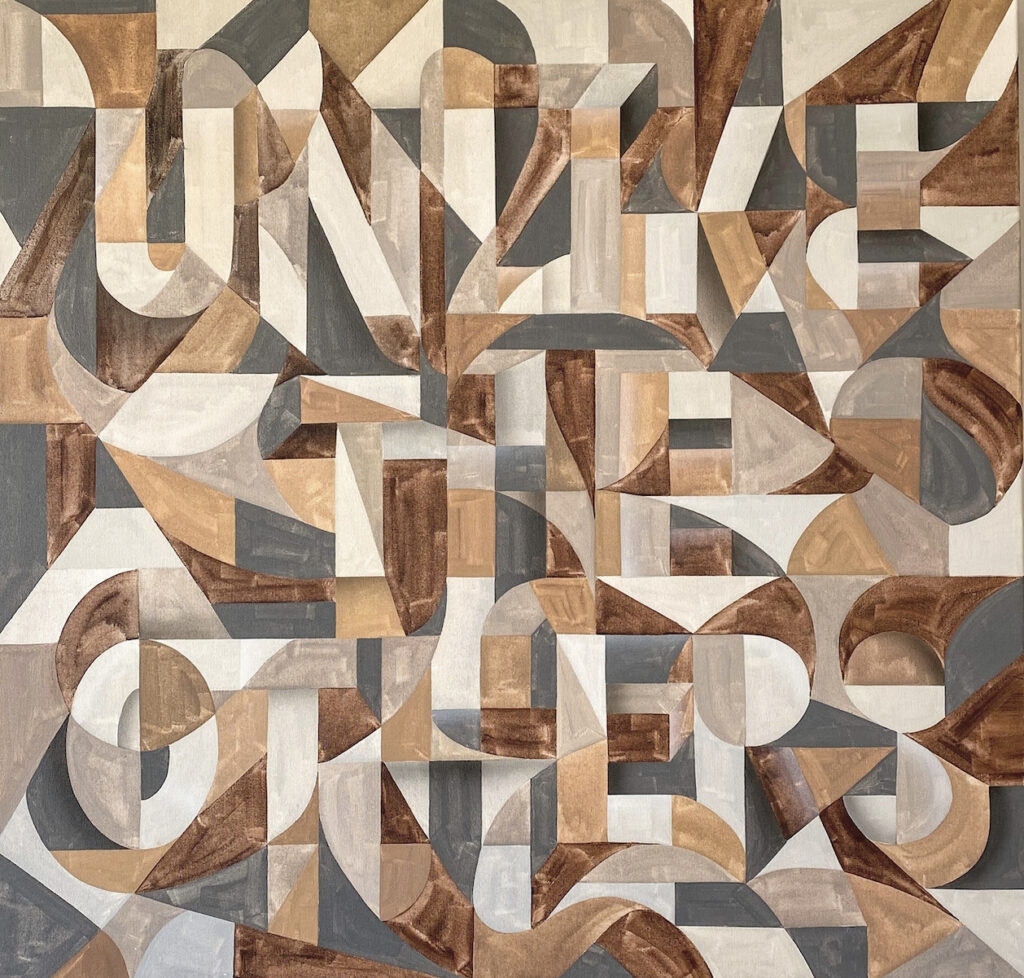

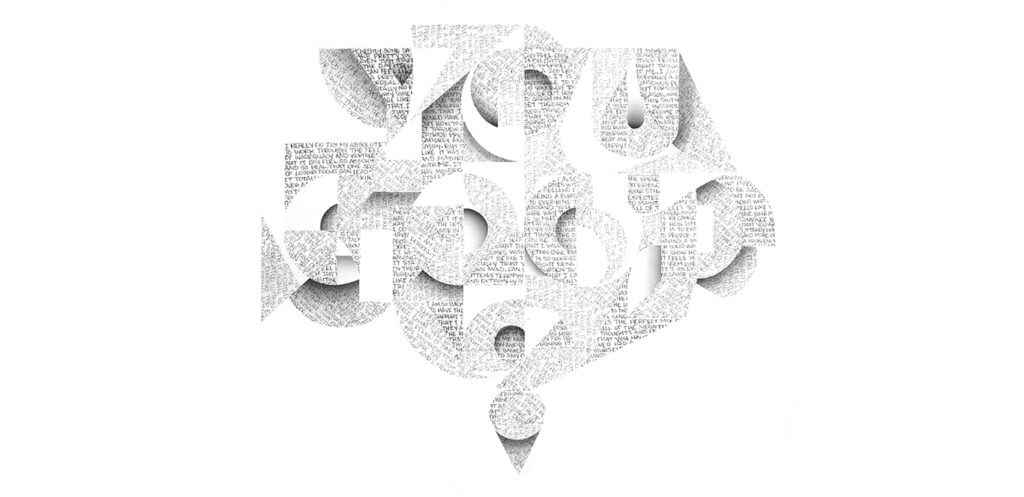

RA: The style of work that I do is letter-centric. It has to do with letterforms, abstraction of letterforms, which comes from my graffiti writing years. It builds from there. [My studio] work has changed in a lot of ways. Coming from graffiti, I was used to the immediacy, but being in the studio, I am able to sit with things longer. [In graffiti work], you have to commit, go, execute, and be done. I still had that mindset when I was bringing my work into the studio. There are even paintings from my residency at Surf Point [Foundation] that I haven’t even finished yet. I’m still looking at them and thinking about how to add to them. I’ve also had a lot of development on the technical side of things, especially now that I’ve been taking my time. I’ve been trying different techniques and experimenting more. I’m not as afraid to get weird.

Even when it got to the point when I was thinking about potentially doing art as a career, I really wanted something that was recognizable and aesthetically [strong]. But I’ve always been a big fan of precision, but now I’m loosening up, which I think just comes with time and confidence. The fear of failure is gone–not because I didn’t fail, but more because I now understand that failure is part of the process. Because of that, there’s been a lot of growth.

TH: That’s so good. Then, continuing with the first question, my second question is, when thinking about the past few years, how has your work and your understanding of your work evolved–especially considering we’ve spent the past couple years in a pandemic and within extremely heightened times and conversations around race, politics, civil and human rights, all of the different things.

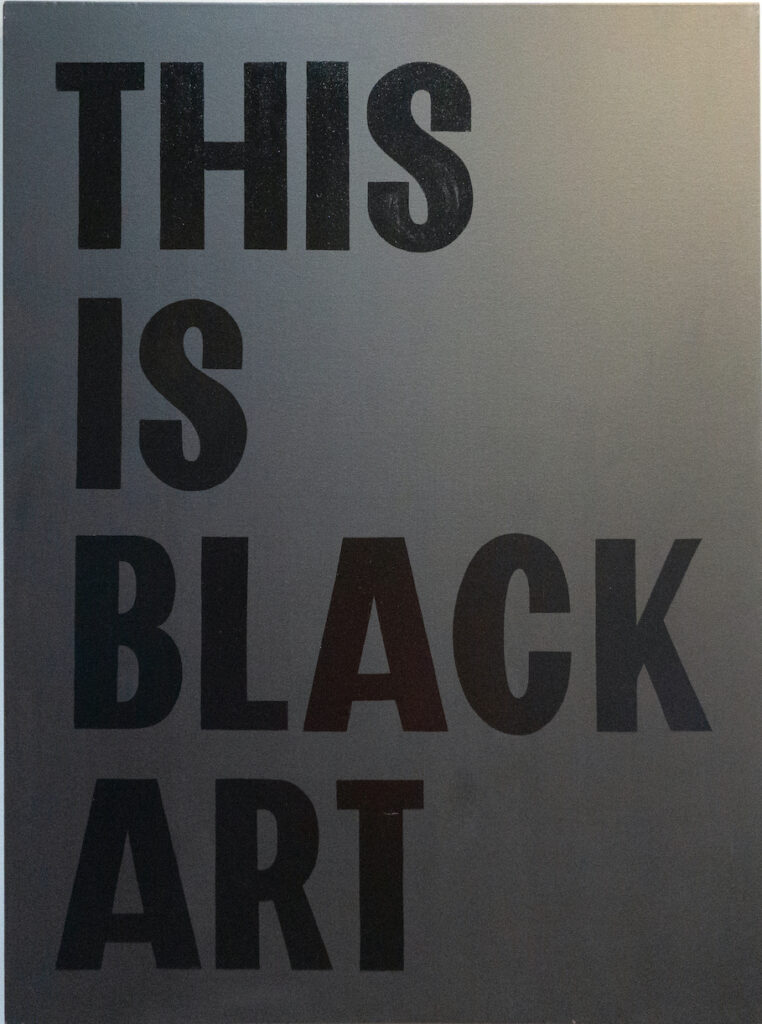

RA: I quit my corporate day job in February 2020. I had everything planned for the Spring and Summer, then everything crashed and we went into quarantine. Fortunately, I was able to make it through. During this same time we also had the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor happening, and there was a shift happening in American culture. The things that were happening to Black folks were highlighted. While it didn’t necessarily affect my work, it had an affect on my life. There was a surge of institutions, corporations, and media folks who started to recognize that they’d been overlooking Black creatives for years. They started to recognize that we are here, and we’re good! There was an onslaught of press and opportunities–all of the things that came along with [this cultural and social shift].

For years, I was working my ass off but would see my white contemporaries and other artists getting opportunities, and [I wasn’t], which made me believe that my work just wasn’t there yet and that I needed to stay focused and work on my style. But then, overnight, I started getting these invitations and institutions and corporations suddenly] saying, “You deserve to be here.”

I did a portrait of George Floyd in downtown Portland that garnered a lot of attention. A lot of those institutions and corporations started to zoom in on that [mural]. [Even with how complicated this sudden attention was], I did start to recognize the power of the work I was doing. I don’t say that to be big-headed, but to mean that when I make and finish murals, I forget that they have a whole life after they’re done. With the George Floyd mural, so many people interacted with this in their own way and had experiences with this work that I will never know about and will affect them in different ways. [It helped me remember that] I’m in the work, my soul is always in the work, and I don’t have to overly worry about who it will or won’t please.

TH: What you’re saying is so interesting for so many reasons, but one of the things what you’re saying makes me think about is value systems, especially when it comes to the records we keep, what we document, what we cherish, and what we historicize or write into history and how all of these things are expressions of value–it’s something I think about quite a bit. If we trusted and focused on the histories and cultural canons that are primarily circulated [in the United States] and, frankly, forced upon us through the education system, media, and other vehicles for information–ones that have been shaped by colonizers and colonialism–we wouldn’t have an accurate sense of the work that we’re doing as Black artists, our contributions, and how profound our work is. It’s an important thing to bring up and remember because in those moments when you’re tricked into saying, “Well, maybe my work just isn’t there yet,” you can remember that chronic systemic issues are what have you thinking that because it doesn’t value your work. By design, we’re in systems that don’t know how to understand and value your work.

So, to me it’s vexing to have this quick shift during this political climate where people, institutions, and companies are technically expressing value–by asking every Black artist they can Google and get their hands on to do everything and be at every event and suddenly be the face of their first-ever all-Black and Blackcentric programming. It really messes with how we as Black creatives understand our own value. At the end of the day, the expressions of value created by these institutional or corporate expressions are made to make us believe that they are expressing value for an artist, community, experience, or particular perspective when, in fact, it is just an optics opportunity for these organizations so that they can cover their asses, check those anti-racist or diversity boxes, and not be caught on the “wrong side of history.”

It’s interesting to think about it on that level, but also on the individual artist level because it impacts and skews how we each understand our creative power.

RA: Luckily, my wife Rachel and I went through it together. We were going through the same thing [as artists]. I should have saved some of the requests that came in because it was clear when people had no understanding of what we did as artists [but just saw that we were Black]. I don’t want to be pessimistic, but my faith that the powers that be have our best interest in mind is non-existent. I suspected that this would be a [temporary influx of interest], but [a dose of skepticism has] really helped me during this time. It was so frustrating. But I landed on the same point that you’re making–they don’t understand how to value what I’m doing, and now I go into it being fully aware of that.

I only expect them to understand my work to a certain point. For instance, I place massive importance on 1970s and 1980s graffiti movements by Black and Brown kids in inner-cities. They are the ones that influenced me and my work, I’m using techniques in my work that they started. And the people offering up these opportunities have no idea, they don’t know these parts [of my work]. Being aware of that has been important.

TH: Graffiti and murals have a long history, so it’s not as if there’s a “resurgence” of these art forms. It’s always been present and significant, especially for those who have been part of its movements and evolutions–like yourself.

At the same time, these are forms that are closely linked to social and political movements–public art, graffiti, and murals are very much an expression, articulation, and document of what’s happening in our worlds and our lives. We are in a very wild period and fever pitch of social, political, and environmental issues, and attacks on human rights. Naturally, murals and graffiti related to these things are also rising higher. Anywhere I go, different graffiti artists and muralists will have different responses, but from your vantage point, where are murals and graffiti at right now as an art form?

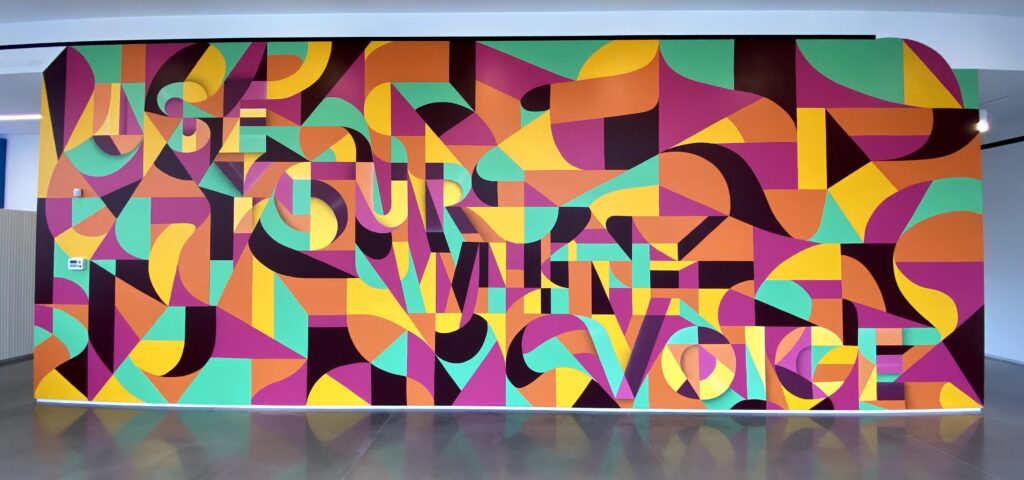

RA: Great question–and I appreciate that you separated murals from graffiti. They are not the same thing! I’ll start with murals. You touched on a pretty important piece which is that they’ve been a voice from within the community, representing the community or a singular person within a community. Over the last few years when everything was shut down, murals and public art played a very big role in communities. I’m sure you saw murals with words of positivity, saying that we’re going to get through this even when confined to our spaces. Or ones that were speaking out to what was happening politically at the time. The importance of murals is a little more understood these days. Then there’s Instagram. From a business standpoint, social media has made these businesses understand that if they have good art, it attracts people to your space and it becomes a kind of landmark. There was a time when you really had to sell people on getting a mural done, but now the general public are starting to understand the value they can bring. It’s wild to watch, especially because I’ve seen it through a few phases.

It’s also phenomenal and worth noting that it’s grown so much, it can be a profession. You can travel and make your work. I love seeing that. But there are downsides, as there are with everything. Like when large corporations get into these things, especially when they take the reins as opposed to letting the artist just make the work. But if more artists are given opportunities to make work that isn’t compromising [their personal and creative integrity], then I’m all for it.

Graffiti is a little bit more of a hot topic. I’ve personally been removed from writing graffiti for years now–I miss it a lot. But it’s just not working with where I am in life. It is something that is youthful and I’m no longer there [laugh]. But it’s wild to see wider acceptance of graffiti. People still get in trouble for doing it, [but today is different than it was before]. In the past, I knew [artists] who would have cases built against them.

[The authorities] would follow you and try to put you in jail for as long as they could, for you writing graffiti. During the pandemic, following graffiti artists slid down the list of priorities. And now there’s a whole generation that is seeing it on their phones and on the streets. And now it’s being brought into art institutions–it’s wild to see. At the risk of sounding like the old head, it was so elusive and difficult to find any information about the world of graffiti–and it was that way for a reason, because it’s very dangerous. While [some parts of the shift are cool], it’s really baffling to watch and not the world I was in when I was in it.

TH: Thank you for talking through that. It makes me want to go back to the topic of value. I’ve always been interested in the conversation that can be had around how the public value of rebellious, anti-capitalist, fiercely independent, and resistant art forms shifts–especially when it becomes identified by certain folks as a tool of capitalism, which essentially weakens or erases the original purpose and spirit of it. We’ve seen it go from devalued and tangled in punitive and carceral systems that prioritize the protection of property (which leads back to what you’re saying about cases being built against artists) to artists being called on to basically help increase property value and business revenue. I’m always watching and trying to understand these shifts, especially as an eternal skeptic.

My last question is a lofty and dreamy one. The future is always uncertain, but we just had the equinox recently, which signals a season change, and we’re going into hibernation and incubation period. We’re in that time of year when we turn inward. If you could make a prediction, what do you think this period will be for you?

RA: I have a show coming up in a couple of weeks and then another in January [2023], so my goal is to really spend time in the studio during the winter season. Spring through fall is essentially a blur for me with murals–being in the Northeast, we only have so long to do outdoor projects. So, when that’s happening, I don’t get much time in the studio. I’m looking forward to studio time because that’s where the growth happens and the next idea comes from.

But also, I realized about a year ago how much I enjoy being able to help provide opportunities for other artists. It’s pretty amazing to see other artists be able to get new jobs and grow [in part because of my help]. So, I’m starting to think about next steps for what that looks like. Mural painting is very physical work, so I’m thinking a lot about what’s next, and I think that might be providing or facilitating opportunities for other artists. I don’t know what form it’s going to take, but that’s the direction I’m facing right now.

TH: I think your story as an artist over the past few years has been a reflection of where we’re at right now. You’ve taken a leap of faith on yourself, stood on your own, started calling your own shots, and have really started to see the beauty that can come from valuing yourself. Thank you for sharing your story and your practice. I’m such a fan of your work.

RA: Thank you for taking the time–it’s such an honor. At a very base level, I’ve started realizing how important it is to have these kinds of things documented. This is how future generations are going to understand these histories. Things like graffiti aren’t always [thoroughly] documented–you really had to search for it. So, I really value you.

TH: Same! And thank you to the Indigo Arts Alliance fam who are forever out here making connections and building relationships!

RYAN ADAMS

Ryan Adams is a painter and muralist residing in his hometown of Portland, Maine with his wife, Rachel Gloria and their two daughters. His background in traditional graffiti led him to creating large-scale mural work and hand lettered design and signage. His signature ‘gem’ style of work is a geometric breakdown of letterforms with shadows and highlights included to create depth and movement throughout the pieces. His pieces tend to be bold, colorful and clever; often including statements within. Currently, Ryan co-owns and operates a hand painted signage business, designs for a brewery, paints murals any and everywhere and exhibits his work as often as possible.

TEMPESTT HAZEL

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center, a collective of writers, artists, curators, librarians, and archivists who have published and produced collaborative projects about artists, archival practice, and culture in the Midwest since 2010. Across her practices and through Sixty, Tempestt has worked alongside artists, organizers, grantmakers, and cultural workers to explore solidarity economies, cooperative models, archival practice, future canon creation, and systems change in and through the arts. An especially cherished moment for Tempestt was when she received the 2019 J. Franklin Jameson Archival Advocacy Award from the Society of American Archivists, which was the result of a nomination by archivists and members of The Blackivists. Tempestt was born and raised in Peoria, Illinois, spent several years in the California Bay Area, and has called Chicago her second home for over 13 years.

Edited by Samaa Abdurraquib

Samaa Abdurraqib is a writer and a poet living in Maine’s Midcoast. She is the editor of From Root to Seed: Black, Brown, and Indigenous Poet Write the Northeast (forthcoming). Her poetry can be found in Cider Press Review and Obsidian: Literature and Arts in the African Diaspora.