Valerie Boyd and

Samaa Abdurraqib

Illuminating a Path

From the ages of 14 to 22, I wrote poetry regularly and with a burning intensity. When I was in the 10th grade, I had a mentor, an English teacher, who convinced me that my poetry was good enough to share with the world—an idea I had never conceived of. I followed her advice and my life rapidly changed. I submitted my writing to local and regional writing contests where I performed well. In 11th grade, I was accepted into a two-week writing retreat at Kenyon College, where I was mentored in poetry and short storywriting. In 11th and 12th grade, my poetry was published in our school publication. My senior year, I was awarded first place in a schoolwide poetry competition, stunning my classmate—a young white woman—who had regularly won this award in the past. I will never forget her face when my name was called at the assembly instead of hers. My path to all of my writing growths and gains has always been flanked by mentors and people who have encouraged me to develop in this particular way.

I have been privileged in my writing life. I grew up surrounded by a diverse array of books and writers. I grew up in a house with a mother who was a writer and two parents who both had a reverence for the written word. Despite all of this—the early love of words;

the early support of mentors; the early immersion in the written word—I sometimes still find it difficult to claim the title of “writer” or “poet.” I sometimes struggle to wrap my mind around what my writing has to offer the world. I have also been privileged in my life to be able to work on a variety of writing projects and to hone my writing craft in different contexts. I have published scholarly articles and book chapters; I have published “think pieces”; I have published pieces of personal narrative. My list of publications is not particularly long or wide, but it does reflect a life oriented towards the written word. In 2017, I made a return to the first form of writing that brought so much meaning to my life as a younger person: poetry.

My return to poetry, twenty years after leaving the form in favor of other forms of writing, was a deliberate and pointed return. The ignition story is simple: in May 2017, I took my first trip to New Mexico with my partner at the time. While we were on the road traveling to the tiny town of Magdalena, I saw an oryx roaming the desert plain, and I had to pull the car over to study this clearly out-of-place animal because it took my breath away. I was so puzzled by its existence in this southern U.S. state. Shortly after that encounter, a poem about the encounter popped into my head, almost fully formed. That kind of visitation hadn’t happened in two decades—it felt pivotal. I have been writing poetry regularly since that moment, and, unlike my previous time with poetry, I have made a commitment to myself to share my poetry, no matter what. I have dubbed this exercise my “Vulnerability Project,” the shape of which is too much to delve into in a detailed way here, but I will say that my commitment to myself has led to a blossoming of opportunity in my life, including public readings, publications, and nourishing connections with a world of writers and artists. The impetus for this Vulnerability Project was recognizing that, for me, vulnerability had to be a practice. Receiving the vulnerability of others has always been a gift of mine, but I have often struggled to respond to the vulnerability of others with my own. I have always admired the strength bound up in vulnerability and I wanted to push myself to move beyond my particular struggles. Sharing my poetry—a private practice of my younger years—seemed like a good place to focus my energy in this endeavor. At the heart of my Vulnerability Project is my hope to create poetry that conveys some truths about my interactions with grief, loss, identity, and wonder. As such, my poetry tends to grapple with the visceral, the puzzling, and the concreteness of experience.

When Marcia Minter invited me to be an artist-in-residence at Indigo Arts Alliance, she and I were sitting together and she asked me if I would be interested in working with Valerie Boyd as her mentee. I was flattered and floored. My mouth immediately said yes, but I was unsure what a written word artist would be able to add to this residency project. I wondered if I, as a writer, would be a good fit in Indigo’s stunning lineup of visual, musical, and textile artists.

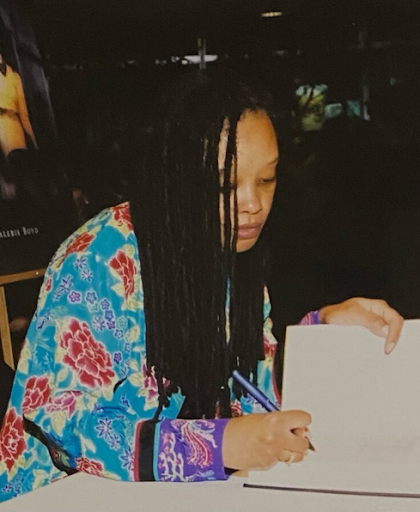

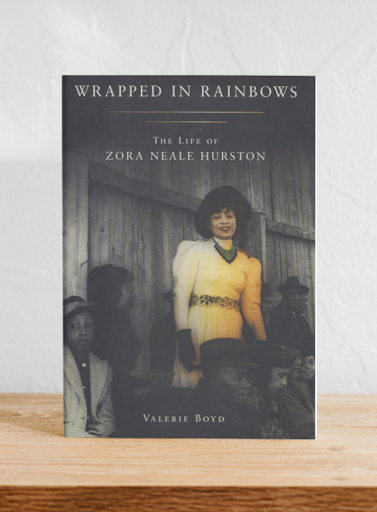

While I was unsure about my fit for the AIR program, I had no doubts about Valerie’s inclusion in Indigo’s line-up, despite the fact that she was also the first writer to be invited as an artist into the program. Valerie Boyd was an Associate Professor of Journalism at the University of Georgia. She was also the Charlayne Hunter-Gault Distinguished Writer in Residence at the same institution. The significance of her writing and her work is SOMETHING. In addition to writing and publishing extensively on race and culture throughout her life, she founded two separate journals, and published the widely acclaimed biography of writer and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, called Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston.[1] While at University of Georgia, she founded a low residency MFA program in Narrative Nonfiction.

I accepted Marcia’s offer of the residency and time to focus on my writing. I was ecstatic to work with Valerie. Since returning to writing, I had found mentorship in wonderfully surprising places, but I had not yet found a relationship where writing mentorship was the primary reason for connection. My time with Valerie was punctuated by pivots and trust. The residency was originally designed to be in-person. Valerie was initially going to travel from Georgia to spend the summer in Maine, at Indigo. When COVID-19 hit the U.S. in early 2020, it quickly became clear that traveling wasn’t going to be an easy and viable option. Indigo made the wise decision to convert Valerie’s residency to a virtual one. When the two of us, in conjunction with Indigo, had to reconfigure our time in residence, we resolved to prioritize flexibility and openness.

There is something about art and connection that is always needed, but especially in times of isolation and distress. And early 2020 was, beyond a doubt, a time of isolation and distress. By May that year, we were all approximately three months into a global pandemic. Many of us had spent the majority of the spring months stuck inside our homes, cut off from our broader communities. Some of us were able to find connection through virtual outlets; some of us shut down completely. We were all in need of spiritual and emotional revival and rejuvenation. People need to be stunned into silence and awe by the beauty of color and the touch of texture. People need to find themselves preoccupied by wonder by the mechanics of the construction of a piece of art they’re standing in front of. The significance and importance of that exchange felt very clear to me. I was unsure about how my words might contribute to this current moment of unrest, fear, and anxiety. Not because my words themselves didn’t have value and couldn’t find resonance with other people—my lack of certainty was wrapped up in ideas about tangibility and accessibility. I often feel that more tangible art (read: visual or tactile) provides a more immediate (read: accessible) response. In my mind, writing is reflective and requires reflection. I wondered if what people needed right then was to be immediately transported from whatever state we’d been muddling through for months.

2020 was full of surprises beyond the Indigo residency. 2020 also brought an invitation into a cycle of the Maine-based artistic collaboration called A Clearing.[2] Each year, the founders of A Clearing— Alana Dao and meg willing—select a piece of artwork and invite (through application) a cohort of artists to use their crafts in order to respond to that artwork. In 2020, Alana and meg selected, fittingly, an apocalypse poem by Franny Choi called “The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On.”[3] At the end of each cycle of A Clearing, the chosen artists are required to produce and make available a piece of art that they worked on during the cycle. As a writer, I once again found myself questioning what I could contribute to the cycle. I realized that I could produce a chapbook. This felt daring for me.

I had never even considered self-publishing; I had no idea where to begin. I had no idea if a chapbook was the right response to the many apocalypses we were all experiencing right in that moment.

The timing of my AIR experience could not have been more perfect. My acceptance into A Clearing had placed this chapbook on my lap, and I was in need of the mentorship that Valerie could provide to move the project forward. I told Valerie about my chapbook project and, without hesitation, she responded by telling me that I could ask her anything and everything about book publishing. This generosity and openness on Valerie’s part allowed me to let go of my uncertainty with this new-to-me process of publishing a chapbook. I wholeheartedly took her up on her offer. When I had questions about the cover design, I reached out to her; when I was preparing to sign the contract with A Clearing, I reached out to her; when I had questions about submitting pieces from the chapbook for publication in poetry journals, I reached out to her. Every time I reached out to her, she responded truthfully and transparently. She told me about her experiences publishing and about how to advocate for myself with publishers. She gave me suggestions about how to create the strongest collection with the poetry that I’d selected. She reminded me to always have an eye towards my next poetry project—which instilled in me confidence to look beyond this chapbook project and towards a full length manuscript. The virtual nature of our connection gave me the space and time I needed to gather my thoughts and questions before I presented them to her. It also gave us space to set meetings on our own terms.

This, I think, is the power of a mentor. They are able to mirror a reality back to you that you sometimes can’t see. They’re able to help you name the work that you’re doing when you’re not really sure about what you’re doing. They have the ability to illuminate a path that you’re already on, when you are maybe unsure of where you’re stepping.

The other component of the residency—i.e., the work that I took on—involved organizing two separate Zoom-based conversations with Valerie as the host. The first conversation was for a closed group of BIPOC writers across Maine. For this conversation, I worked with Indigo staff to curate a list of experienced and new BIPOC writers in Maine who wanted to be in conversation with Valerie about any and all stages of the writing process. The curating process had wide and impactful benefits. While Indigo openly embraces BIPOC people engaging with all forms of artistic expression, their connections with BIPOC writers were not as robust as their connections with visual artists. Assembling a group for the private conversation with Valerie gave me an opportunity to dig into my network of BIPOC Maine writers, and put them in more direct contact with the vibrant Indigo community.

In preparation for the conversation, Valerie asked me to poll the interested writers to get a sense of where they were on their writing journeys and to determine what sort of focus would be most helpful. What emerged was a diverse range of writers—poets, playwrights, essayists, novelists—situated broadly across the writing spectrum. Some were hoping to create new writing; some were actively searching for publishing homes for their work; others were just curious about the publication process. The breadth of Valerie’s knowledge and experience shone through in this conversation as she deftly navigated the diverse range of questions from the group of eleven writers.

The second conversation was a public panel with a group of writers hand selected by Valerie. The panel, hosted in July 2020, titled “Writing the Revolution. Conversations: Writers Across Genres Speak on the Current Pandemic and Uprising,” featured photographer and novelist Craig Seymour, television writer and executive producer Valerie Wood, and playwright and novelist Shay Youngblood. Valerie moderated. The writers discussed the important need for our writing in this current moment, but also the need for writers to balance production with rest. All of the panelists acknowledged that they had been struggling to write at different times during the pandemic, an acknowledgement that felt welcoming to my ears and to the ears of the attendees. It seemed important to mention the struggle to write because so many of us writers were experiencing similar blockages. It felt affirming to be linked with these prolific and experienced writers in this way. This acknowledgement also drove home the importance of resting and waiting for the writing to come as it may—our words would be important whenever they arrived. These group conversations, with Valerie at the helm, helped bring home the importance of the written word in this moment

My work with Valerie during Indigo’s AIR program was a gift of mentorship and focus. It allowed me to fully see and understand the value of my work. The focused time with Valerie gave me space to see the value of my Vulnerability Project and to better articulate the work my words are doing in the world. I’m still not fully sure where this project will take me or where it will end, but the reverberations of the project have been so very beautiful—as I feel my strength grow in the areas of my vulnerability, I can see how my words resonate with and move others, and that is wonderful reward.

Valerie Boyd

Valerie Boyd was the author of the critically acclaimed biography Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston, winner of the Southern Book Award and the American Library Association’s Notable Book Award. Wrapped in Rainbows was hailed by Alice Walker as “magnificent” and “extraordinary”; by the Boston Globe as “elegant and exhilarating”; and by the Denver Post as “a rich, rich read.” Formerly arts editor at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Boyd has written articles, essays and reviews for such publications as The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, Creative Nonfiction, The Oxford American, Paste, Ms., Essence, and Atlanta Magazine. She was a professor of journalism and the Charlayne Hunter-Gault Distinguished Writer in Residence at the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia, where she founded and directed the low-residency MFA Program in Narrative Nonfiction. During her residency at Indigo Arts Alliance in 2020, Boyd was working on a collection of essays, Bigger Than Bravery: Black Resilience and Reclamation in a Time of Pandemic. It will be published by Lookout Books in Fall 2022.

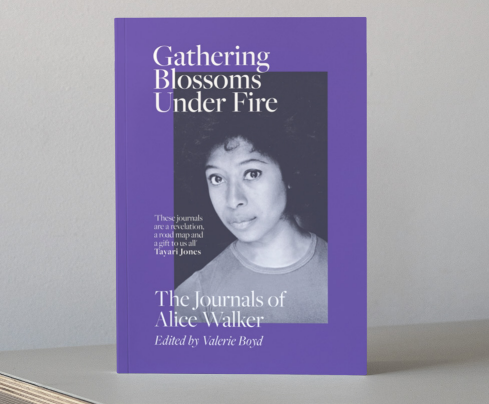

Her latest book, Gathering Blossoms Under Fire: The Journals of Alice Walker is releasing this Spring 2022. This epic work draws from the personal journals of Alice Walker spanning more than 50 years and created in collaboration with Ms. Walker. Published by Simon & Schuster/37 Ink.

In addition to being an acclaimed author and educator, during her lifetime Valerie Boyd encouraged a generation of young writers, predominantly women of color, to pursue careers in nonfiction. Boyd also served as an advisor to Indigo Arts Alliance, with her vision and wisdom helping to propel our organization forward. The ancestors have surely welcomed her powerful Black feminist spirit.

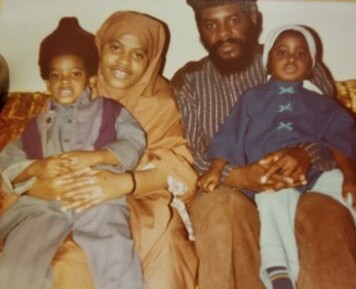

Samaa Abdurraqib

Samaa Abdurraqib was raised in the Land of Buckeyes (Ohio), spent 8 years in the Land of Dairy (Wisconsin), and moved to the Land of Lobsters in August 2010. She spent three years teaching Gender & Women’s Studies at Bowdoin College and transitioned into the non-profit world in 2013 and has been on that grind ever since. Samaa currently works at the Maine Coalition to End Domestic Violence. She enjoys birding, hiking and being outdoors, facilitating reading groups for the Maine Humanities Council, and coaching leaders of color. Some of her academic writing can be found in the edited collections Teaching Against Islamophobia (2010), Muslim Voices in School (2009), and Bad Girls and Transgressive Women in Popular Television, Fiction, and Film (2017). Her non-academic writing has appeared in I Speak For Myself: American Women on Being Muslim (2011) and the online magazine The Body Is Not An Apology. Her poem, “End of Land – Deer Isle” was recently published (2020) in Maine Coast Heritage Trust’s Voices From the Coast – a publication celebrating the organization’s 50th anniversary.

Edited by Jenna Crowder

Jenna Crowder is a writer and editor. Her writing has appeared in

Art Papers, Boston Art Review, The Brooklyn Rail, BURNAWAY,

Temporary Art Review, and The Rib, among other places.

jennacrowder.com